By Michael Gormley

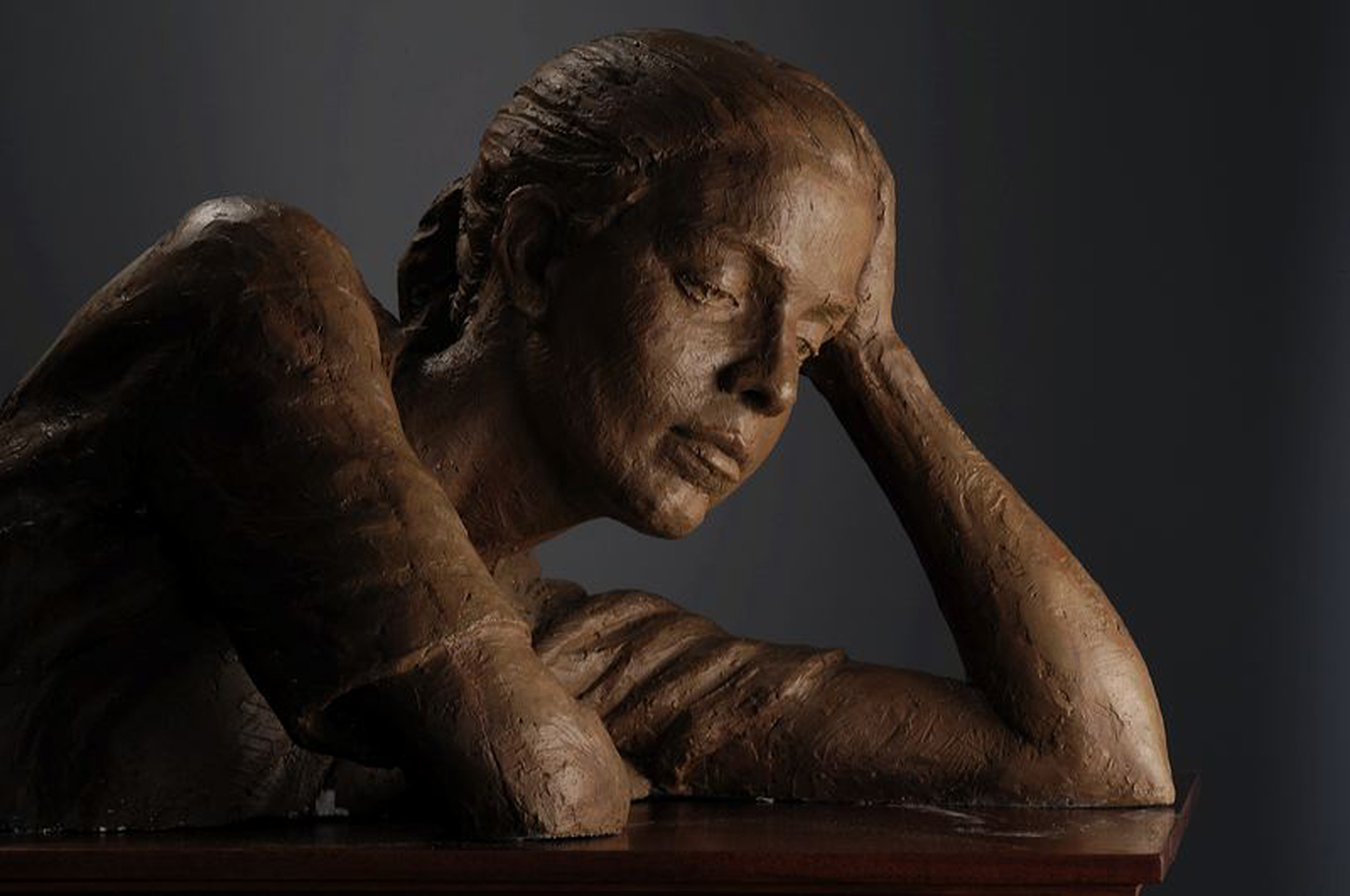

Alan LeQuire, Farrar, painted plaster cast, life-size

Note: This article is part I in a series featuring sculptors represented by Portraits, Inc.

Nothing gets our attention faster than art which portrays life-like images of the human form—be that a drawing, painting or sculpture. The latter trumps all with its power to enchant—likely because, out of the three, sculpture most closely approximates our worldly existence. Sculpture doesn’t just hang around on a wall—it has weight, volume and takes up space—just like us. And then there is the added expressive element offered by scale; sculpture wows whether it is diminutive or as big as a house—we find both exaggerations equally alluring.

Sculpture’s powerful allure has long been recognized as a potent force to be celebrated—but also proscribed. Hence it’s no accident that our culture’s social, religious, and civic institutions have historically provided sculpture practitioners with the bulk of their commissions—and thereby steward the production of images meant for public viewing. “Iconography” is a notable and persuasive cultural communicator to the point that sculptural imagery can portray specific values and belief systems—in addition to capturing the likeness of a specific individual. This trope explains why we have a monument to Lincoln and, on the flip side, why public sculpture is the first thing that status quo dissenters take aim at when major shifts in culture occur—for example, toppling Lenin’s statue. What is important about these works are the ideas they represent—they are our cultural containers holding what we collectively cherish or abhor.

The reliance on institutional patronage for sculpture production also stems from practical needs. Sculpture requires an enormous investment of time, skill and material resources—even modestly scaled works are subject to a carefully staged production process. Sculpture is created either by subtractive or additive method. Clay works are built up—hence it is “additive.” Stone or wood are carved, work that removes mass from the starting material—it is a “subtractive” process. The focus on this post will be on the additive method. A sculptor working in this method generally begins his piece by creating a small clay model—alternately called a maquette (French) or modello (Italian). The equivalent process would be the initial sketches a painter makes to explore compositional strategies or figure arrangements. Composition is a complex design problem in sculpture. With the exception of shallow wall-mounted friezes, a sculpture’s final design must work in the round—since it can be viewed from multiple angles. Each vantage point needs to aesthetically pleasing—both visually and kinesthetically. Remember, sculpture takes up space.

To arrive at a pleasing design, a sculptor shapes his material into convex and concave forms to create expressive passages of light and shadow. Most sculptural works are monochromatic and, though they display the surface effects characteristic of the material they are made with (be that earth, stone or metal), it is foremost the dramatic play of light against dark that holds the viewer's eye and guides it through the work. The use of strong contrasting values informs many of our most cherished masterpieces and can be traced back to the Italian Renaissance. The technique was called chiaroscuro, Italian for "light-dark," and it provided a means to represent graphically, or three dimensionally, the perception of mass and volume created by light traveling across form.

Second to chiaroscuro in signifying a life-like presence is figure gesture and rhythm. Similar to contrasting passages of light against dark, realistic figurative sculptures strike a balance between tension and repose. The Italians called this technique contrapposto. Artists had noted in their observational drawings of the life model that the human body tends to shift its weight and balance from one side to the other—such the left and right sides of the body are alternately active or resting. By composing their figures such that one side appeared to be weight bearing, they were able to re-create a life-like presence in their work. By further studying anatomy, artists were soon able to depict natural poses and life-like proportions. Approaching modern times, artists experimented with exaggerating human gestures and proportions to achieve expressive effects.

Having utilized the above noted techniques to create a maquette, a sculptor working on a large scale work will create a full scale clay model with the added aim of refining the original design. For a work that may ultimately be cast in metal , a plaster cast is first made from the clay model using rubber or silicone molds that are attached in pieces and then assembled into a whole. This process rarely leaves the clay model intact—so it is fraught with complications. If the work is not being cast in metal, many sculptors paint the plaster to create a patina that imitates bronze—the result is often striking and appears to be the real thing.

Metal casting, generally using bronze, is an art unto itself and most sculptors work with a foundry which employs highly skilled artisans. Using a method called “lost wax” or “waste mold,” a rubber piece mold is formed over a plaster cast. The rubber mold is then used to create a replica of the original plaster cast—this time a hollow wax or paraffin cast. A fireproof mold is then shaped over the wax cast—this mold is then heated and the wax made to run off though specially designed drain channels in the mold. Into this now empty mold is poured heated molten bronze. Finally the metal casting is “chased” with a heated metal tool to file down imperfections left from the casting process and the surface of the sculpture is finely polished.

Alan LeQuire is a bronze sculptor represented by Portraits, Inc. He is well known for working in a wide range of sizes—from miniature to monumental—and for meeting the specific needs of his clients, be they notable institutions honoring a major donor or proud parents wanting a likeness of their beloved child. By nature adaptable and inquisitive, LeQuire approaches each commission with fresh eyes and an open mind. He notes, “I am adept at creating traditional portrait busts—and sometimes this is the best solution for a commission. In other instances I need to find new ways of interpreting the proposed portrait and I find that challenge has inspired me to create my best pieces.

“Farrar,” pictured above, offers an example of LeQuire’s inventiveness; in this instance he creates, through expressive pose and gesture, a wistful narrative of a young woman in reverie. One needn’t know the sitter personally to recognize her – this fact matters little as she has come to represent not just one person but many—an identifiable archetype. Hence the work's power and allure. We look upon her and see the tender remains of passing childhood and the still fragile emergence of adult consciousness. Her present moment is all potential—the promise of a new life and the understanding that great things will come to pass—even those not yet dreamed.

LeQuire generally begins his commissions by making a rough sketch in clay; he waits for the client to approve the overall composition before commencing work on the final portrait. If the commission is for a life-sized or larger figure, he makes a maquette first (a small scale model) for client approval before commencing work on the full-sized piece. He prefers working from life and will arrange at least two sittings for about two hours each time with the subject. If the commission is for a posthumous portrait he can work from available photographs as reference.

LeQuire adds, “I work in clay and cast in plaster and bronze. For clients who don’t have the budget for cast bronze I offer a cast gypsum product that is almost as hard as stone, and can be made to look like terra cotta or bronze. I make my own molds and wax castings in preparation for bronze casting. I take the wax to a foundry and they give me back an unfinished bronze casting. I do the final chasing and the patina myself here in my studio. This gives me a great deal of control over the final surface texture.”

LeQuire received an MFA from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro in 1981 and completed a BS at Vanderbilt in 1978. Specific training as a sculptor came through a series of apprenticeships beginning when he was sixteen. His first teacher was Puryear Mims, a noted figurative sculptor who was on the faculty of Vanderbilt University. Mims in turn studied at the Art Students League in New York City. Later LeQuire apprenticed with Milton Hebald in Bracciano, Italy from 1978 to 1979. Hebald was also a student at the League. LeQuire notes, “Hebald helped me move from being a carver to being a modeler in clay. He also trained me to make portraits by first having me make portraits of his cook, his grandchildren and local neighbors. He also helped me get a job working in an art foundry near Rome.”

Figurative sculpture was largely out of favor when LeQuire was a student in the 1970s. It is a testament to his love of portraiture that he soldiered on with his studies and mastered the skills he needed to seek out commissions. “I have always enjoyed portraiture,” LeQuire adds. “I love capturing a likeness because when the inanimate material (clay) takes on the spark of life, it is like watching a miracle happen. To me this is the most direct experience of what I consider to be the central mystery of sculpture.”

To commission a sculpture portrait by Alan LeQuire or other sculptors represented by Portraits, Inc., please contact us.

Michael Gormley is a painter, writer, curator and regular contributor to the Portraits, Inc. blog. Gormley is the former editor of American Artist magazine.