By Michael Gormley

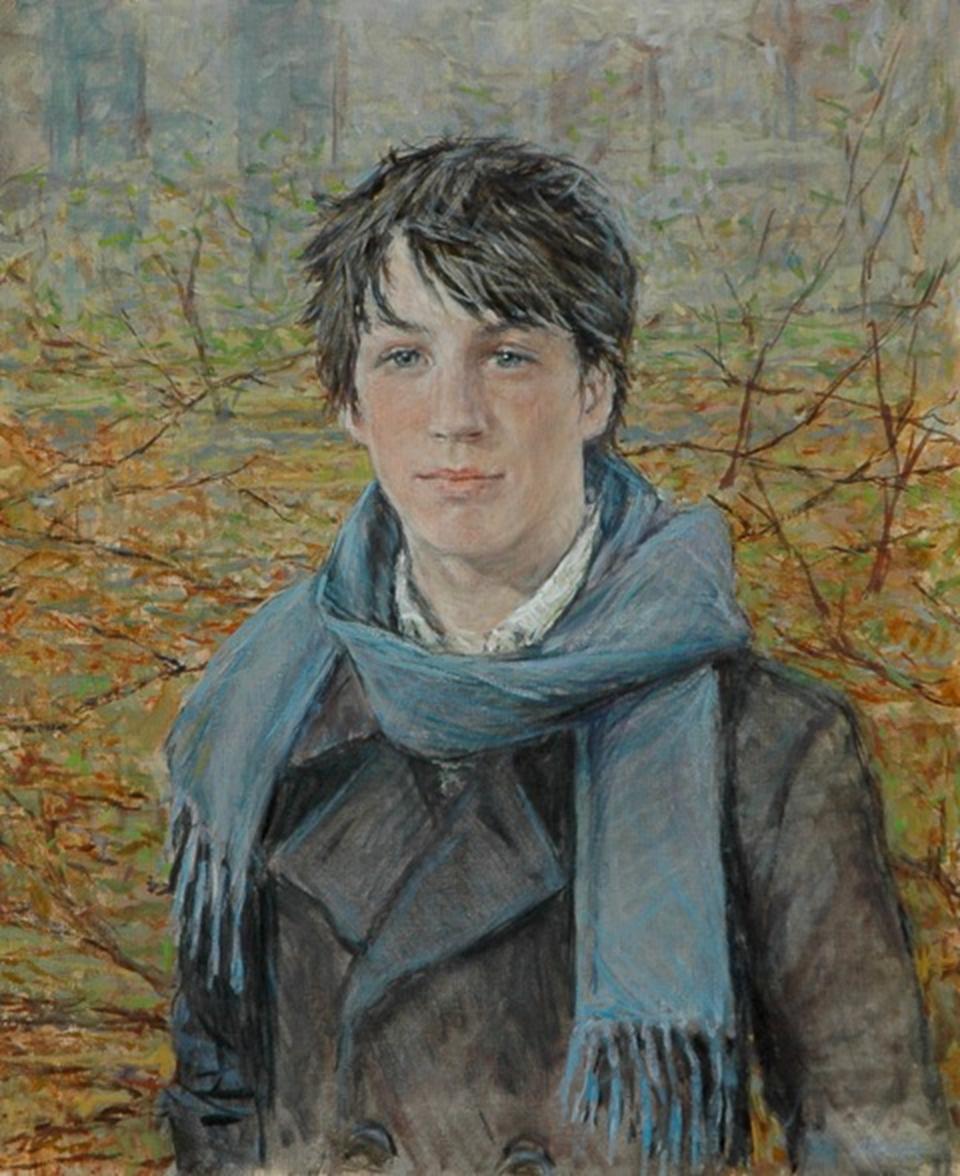

Fielding Archer, Julien, oil on canvas

Since the invention of the camera, portrait artists, and by extension figurative artists, have tended to consider their work in relationship to photography. Realist artists, who had long enjoyed a relative monopoly on image making that portrayed the illusion of life, found the comparison between the two media particularly vexing. In response to the camera, and to the myriad cultural shifts spun from the mechanized juggernaut of modernity, artists began to re-think portraiture and figurative art in order to arrive at a raison d'être for its very existence.

One aesthetic response, a practice that continues up to the present day, aims to beat the camera at its own game—by seeing life as if through a camera lens and creating works that depict images in minute detail. Some artists employ photography to help achieve this end; in fact this practice pre-dates the invention of the modern camera. The camera obscura (Latin: "dark chamber"), an optical device that was a precursor to the camera and light photography, was used to project images onto a drawing or painting surface to trace imagery. Some art historians believe that Jan Vermeer, the quintessential Dutch realist, employed this device in his work. His paintings do have a photo-like quality—especially his highlights which display a heightened and focused glow like one sees in an over-exposed photograph.

Regardless as to whether contemporary artists employ a camera, other optical aides, or simply rely on extraordinary skills to achieve illusionary realism—the important point to consider is the extent to which said artists, and their patrons, view the world, and the work they create to imitate that world, through the lens of a camera. Ponder for a moment this art truism: if a work looks like a photo, then it qualifies as “realism” or is thought to be “life-like”—when in actuality it is “photo-like.” Now create a mental picture of the “realism” practiced before the advent of photography—a painting by da Vinci, Tintoretto or Tiepolo. Would you confuse that manner of representation with the bulk of realism practiced today?

Let’s re-think the idea of what constitutes “real” by exploring an alternate response artists had to the ascendancy of the camera. We may take the view that the latter gave rise to both the Impressionist and Expressionist art movements. We may begin with the premise that artists exploring either motive did so with the understanding that hand-made realism could very well trump the realism delivered by the camera—but opted instead to create imagery that the camera could not. By refuting camera lens vision, Impressionists and Expressionists learned to view the world with fresh eyes and developed an aesthetic language that was primarily optical, decoratively stylized, and emotively charged.

A current exhibition at the Neue Galerie featuring Egon Schiele’s portraits, along with those of his Viennese contemporaries Richard Gerstl, Gustav Klimt and Oskar Kokoschka, demonstrates this then radical view. Their paintings make no effort to capture a photo-like verisimilitude; quite the opposite, their portraits push the boundaries of what we consider representational art to such an extreme that they no longer seem tethered to the natural world. Or do they? Consider the photograph’s knack for capturing surface effects—glass appears brittle, hair falls in soft ringlets. Similarly, realist artists prize the ability to depict the subtleness of flesh and the glint of silver shining against the furry knap of velvet—and rightfully so—that bit of magic ain’t easy. But what lies below the glint, folds and blush of surface? Can that which is hidden be the subject of portrait art? What of your mutable moods, nameless fears and wondrous flights of fancy? Are not your emotional states as “real” to you as your left foot? Is there anything more “natural” to the human condition than states of mind—the manifestations of psyche?

Psychology was big news in 19th-century Vienna—its community of learned scientists and doctors were making enormous strides in their efforts to unlock nature’s secrets—among them the workings of man’s inner life. Works by artists such as Schiele acted as signposts along this road to discovery. His deeply intuitive portrait work was groundbreaking and fearless in its exploration of human character. Schiele saw what his subjects “felt like” rather than what they “looked like”—a vision that ultimately found expression in a unique pictorial style that unabashedly communicated essential truths about the human soul. That said, Schiele’s genius often signaled the grotesque—a difficult style not ideally suited for most contemporary portrait commissions.

But there is a middle road. I would argue for portraits that convey both visual likeness and a rich inner life approach the true meaning of “portrayal”—a work of art meant to represent an individual human soul in all its glorious and imperfect striving. Portraits, Inc. represents a highly select group of contemporary artists able to achieve this level of art. Among these gifted practitioners is Fielding Archer whose portrait of his son Julien, reproduced here, was included in the Portraits, Inc. survey exhibition at the Salmagundi Club in New York City. The work offers an expressive paint handling that stakes out an aesthetic intent—one that disclaims the freeze stillness of photo-realism and replaces it (by using energetic brushwork) with a style emblematic of the rush of life as it is—momentous and ever mutable. The work is poignant – that is clear. Look again; Julien is neither child nor man—like all of life, he is ceasing and becoming all at once. Nature’s ever turning round is made manifest; Julien stands poised among the soon to stir sleeping woods of winter—the barely there green holds great promise; a park soon to be in full bloom—and a beloved son soon to be a man.

As you draw closer to your family and loved ones at this most joyful time of year, rest in the knowledge that what is good and true, in nature and in us all, abides as assuredly as the turn of the seasons. On behalf of Portraits, Inc., I wish you the merriest of holidays and good fortune in the coming year.

Michael Gormley is a painter, writer, curator and regular contributor to the Portraits, Inc. blog. Gormley is the former editor of American Artist magazine and most recently created the fine art catalog for Craftsy--an online education platform.

Portraits, Inc. was founded in 1942 in New York on Park Avenue. Over its 70-year history, Portraits, Inc. has carefully assembled a select group of the world’s foremost portrait artists offering a range of styles and prices. Recognized as the industry leader, Portraits, Inc. provides expert guidance for discerning clients interested in commissioning fine art portraits.